Meet Raymond, a young systems engineer who’s planning to marry his girlfriend Alice next year after dating for 6 years. Raymond is a big believer in insurance—he bought some right after graduating from university. But Alice? She’s got no coverage and is actually quite resistant to the idea. They’ve discussed it several times, and in the end, Raymond decided to get her a comprehensive personal insurance policy that includes life, critical illness, and medical protection. He thought it would be straightforward, but things didn’t go as planned. Why not?

What is Insurable Interest?

Many people have similar experiences—they assume that as long as the policyholder is willing, they can buy insurance for others like a partner or relatives, only to get rejected by the insurance company. It turns out, insurers require something called insurable interest to approve the policy.

So, what exactly is insurable interest? It’s essentially a clear financial or recognized relationship between the policyholder and the insured, such as parent-child bonds that insurers typically accept. Why is this necessary? Insurance is all about compensating for actual losses, not turning a profit. If someone without an insurable interest collects a payout, say from a death benefit, it could violate the core indemnity principle and even create moral hazards—like someone insuring another’s life just to benefit from their misfortune.

What kinds of relationships qualify as insurable interest? It varies by location and insurer, but in Hong Kong, companies generally accept parents insuring children or creditors insuring debtors, with proof like debt amounts required in the latter case. Some policies, like voluntary health insurance, even extend to grandparents or siblings for added flexibility.

The Principle of Indemnity

On the other hand, Alice’s resistance to insurance stems from thinking it’s like gambling, with the policyholder betting against the insurer. In reality, insurance is about transferring your risks to the company, which sets aside reserves to cover claims—they’re not rooting against you.

As mentioned earlier, a key insurance principle is indemnity, meaning you’re only compensated for your actual losses, not extra gains. This sets it apart from gambling entirely. For example, with health insurance, it’s based on actual expenses, so you won’t get more than what you spent, even with multiple policies.

You might wonder: If someone has multiple life insurance policies, couldn’t they get the full payout upon death? Does that break the indemnity rule? Well, it’s tricky because personal losses, like a life, aren’t easily quantified in dollars. To stay true to the spirit, insurers check the purpose and set reasonable limits on coverage—which is why applications ask about other policies you hold.

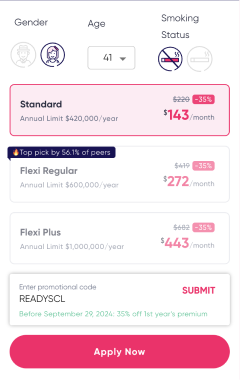

In the end, Alice finally grasped the principles and spirit of insurance, and she was touched by Raymond’s persistence. She decided to get a comprehensive policy in her own name, ensuring solid protection for herself and those who care about her.